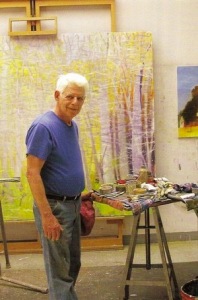

A Conversation with Artist Wolf Kahn

Getting by with a little help from our friends …

Wolf has generously made nine images from his personal collection  available to Story Preservation for our K-12 in-school Learning Lab project.

available to Story Preservation for our K-12 in-school Learning Lab project.

Click on the links below to hear him talk about his childhood in Germany and England, his immigration to America, his years studying under Hans Hofmann, and the evolution of his art. *I’ve included an excerpted transcript from the recording session. See below.

.

Wolf Kahn, Self Portrait with Sombrero, 1954, 22 x 17 inches, Oil on Canvas, Collection of the Artist © Wolf Kahn/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Used with permission.

This makes for a long post but here’s an edited excerpt from the recording:

TRACK 01 – FROM GERMANY TO THE US

My father was the conductor of the Stuttgart Philharmonic. He married – my mother was a strange lady, from what I hear. I think my father – because I am the youngest of my siblings by six years, people have told me that my father made my mother pregnant, because he thought she was moving out of his purviews, you know, and becoming stranger. He thought that if she had a baby that would get her back to reality, and I was the reality. … Well, I think a year after I was born, she just moved out. When she left our house, she told my father to marry a young singer that he was either having an affair with or was interested in, and she left. I was a baby; I think I was three years old at the biggest, when she left the house. My father very quickly married this new wife. She didn’t like me.

I remember one of the earliest stories from my life. We lived in Stuttgart, and Stuttgart is set as a city that is set in a basin. In order to get to the city, you have to walk down interminable steps. I mean, they’ve got roads, naturally, going like this, you know, but for pedestrians, you go down interminable steps. I remember it was before Christmas and my stepmother said to me, “We’re going to go down now to buy you a Christmas present.” And I had no idea what that was all about, but then we got down to the town and she took me to a store where they sold canes. And she bought a cane and said, “If you don’t behave, that’s what you’ll get, and that’s your Christmas present.”

So I could see that she certainly didn’t love me and didn’t even like me; wanted to get rid of me. Fortunately, my father’s mother lived in Frankfurt, which is, you know, a town that’s a couple of hours away, and she wanted to have me live with her. Or else – I don’t know how that worked. But anyway, she got me, much to the envy of my siblings, you know, because they were having a tough time with her, too. Later on, she turned out to be a Nazi.

I certainly wasn’t, at that point, a very happy child. But then, as soon as I was with my grandma, she was a wonderful woman, very strong, experienced in bringing up children, because she had three of her own. We also had in the household — we had Mim, who was a family retainer from England. Her name really was Miss Wilkins, you know, but we all called her Mim. She was very lovely with me too, and taught me English, because she didn’t like to speak German. As soon as I was with my grandmother, I had drawing materials and encouragement, you know. I didn’t have any lessons. I didn’t have them until a good deal later. But I certainly felt like a happy child at that point, you know. We were living right at the entrance of the Botanical Gardens in Frankfurt, and after a heavy rain, my grandmother would take me out and went looking around carefully. She’d tell me to get into the beds where the dahlias were growing and where some huge dahlia had broken off, she told me to take it out, put my raincoat over it, and walk it out of the Botanical Gardens. Then she’d meet her friends, and her friends made a fuss over me, and she didn’t like that, because if they started to say, what a pretty boy – because I was a pretty boy – she’d say, “Shhhh, Ich spreche English.” So she tried to keep me from becoming conceited and arrogant. Of course, she was a total failure at that.

The next very serious thing that happened is that World War II was about to begin. I was 11 years old. People were already being taken to concentration camps, so my grandmother took me to the American Consulate to have me rejoin my family, and they gave me a number, a quota number, because they had in those days the McCarran Act, which gave each nation a quota. The Germans, at that point, had 10,000 a year, and I think they had 300,000 Jews that were still living in Germany at that point. So the English or, in this case, my aunt in London, who had already emigrated much earlier, got me into this program where volunteer families would take these children. So I arrived in England with a tag around my neck. If that hadn’t happened, I’d be a pile of ashes. So that’s my part of history, so to speak.

At a certain point, it looked – you know, they had the Blitzkrieg, and it looked like England was going to be bombed. I lived in Cambridge, which was a target town, because they had factories around there, and laboratories, and the university. So everybody tried to get out who could. And then they also sent people from London to Cambridge, because London was of course the prime target. So my aunt in London arranged that I would be part of a kindertransport. She was successful in getting this family in the suburbs of Cambridge to sign an affidavit that I would never become a charge of the state. That’s what the English were most worried about, with these refugee kids. So I went to stay with them, and they turned out to be terrible people. In advance of my arrival a bicycle, a stamp collection, and a huge trunk arrived, and they didn’t understand that at all for a refugee. You know, you’re supposed to have scurvy and dark around the eyes, and here was this little arrogant kid, who spoke English well and didn’t look like a refugee at all. I was fat, fat-ish anyway. So this professor Wade, as soon as we got home, he said, “Now you speak English and I want you to listen carefully to what I have to say. I want you to come into my study and I’ll tell you what I think.” He says, “I think that your family perpetrated a fraud upon us, and you’re not a refugee at all. And the only way I can protect myself is to make you into a servant in the family. So this is what you’re going to do, you’re going to get up at 5:00 in the morning and shine everybody’s shoes, and collect their laundry, and just generally help the maids.”

They were quite well off, these people. I right away understood that I was not very welcome in that household. Then he put me in the garden to help weed. Of course once you know, as a child, that you’re not being loved, and not being welcomed, you do everything wrong. I was constantly in trouble. So then the war began and Wade became an officer in the Territorial Forces, and he just let the authorities that were in charge of me, the Joint Distribution Committee, a Jewish Organization, know that he wanted to get rid of me. They found a lower-middle class family, the Purvises, who treated me very differently. They put me in school right away, where incidentally I became number one boy in English, in the class, because when I was still in Frankfurt, I was attending a gymnasium, which had all – all the teachers were professors from the university, Jewish professors who lost their jobs. The Jewish community put them in charge of kids in the gymnasium. I learned English grammar to the point of being able to parse any kind of sentence and so forth. Of course the English kids who grew up speaking English didn’t have to do any of these things. So as soon as I got into a class, I started talking about grammar. I was way ahead of everybody. So, in Cambridge, living with the Purvises, I had really quite a good time. I made friends with the English kids. They were interested in me.

The teachers didn’t know how to pronounce my name, because England at that point was a very isolated country. Nobody knew what to do with a name that started with a “K” and had an “h” in it. I mean, these things just don’t occur in England. So they all didn’t quite know what to do with me, but they could see that I was smart and knew my way around the world already. Then, the Americans changed the law, whereby families, Jewish families, could be reunited. When the Blitzkrieg began, and bombs started to drop, it was thought wise to get me out of the country. My father started proceedings with the consulate and so on, in New York, to get me. And my aunt put me on board the Volendam, which is a Dutch boat, where I was put into the charge of the First Mate, who actually liked me a lot and treated me as one should a little 12-year-old kid. He put me up on the bridge part of the day, with binoculars, to look for U-boats. We were traveling in a convoy. It was very slow. I think it took 20 days to get across the ocean. I, of course, felt very important up there with my binoculars. Then we got to Hoboken, which is where the Holland America Line had its dock, and there was nobody there to greet me. I guess the mail that announced that I was coming must have been sunk or something, so the Immigration Service – I guess they got together with the First Mate and he put me in the First Class dining room, where I proceeded to eat ham sandwiches like crazy. Finally, at a certain point, they did contact my father and he came and fetched me.

TRACK 02 – THE HOFMANN YEARS

What happened is that my brother, Peter, also was a good draftsman and very interested in being an artist. He and I sort of became competitors almost. He went into the Army, you know, it was World War II, and I was going to the High School of Music & Art, here in New York. By that time, my father had moved to New York. In the High School of Music & Art, I found out, yeah, I was a bit of a hotshot, even there. What I’d do was I’d make caricatures of the teachers in chalk on the blackboard, before the teacher came in, while the class was waiting for him or her. I was good at caricatures. I would get a lot of resemblance very easily. So that made me quite popular.

I wanted to enlist. It was toward the end of the war, but there was still a whole other year, before the peace with Japan was signed. Germany was still in the war. So I joined the Navy, and I passed the Eddy test. The Eddy test is something where they try and find out whether you’re smart enough to study radar, which was a brand new thing at that moment. I passed the Eddy test, and I found myself in the company of MIT students. I’d never even had physics in high school, so I had a hard time there, in addition to which I was not used to standing watch at night and go to school in the daytime. But I learned how to stand and sleep at the same time, which is a useful thing to know how to do. Then I finally flunked out, especially since the war was – they were becoming more and more selective. I had been doing, while in the RT program, drawings of my friends and also some of the recreation officers and people like that, in the style of Artzybasheff, who was the guy who did the covers for Time Magazine. I was pretty good at faking Artzybasheff and making people look like they should be on the cover of Time Magazine. I had a good time in the Navy, when it comes right down to it. I got out, and then it came time to be on the GI Bill.

I wanted to go to Columbia, but it was too late in the year to enroll there, so I went to New School in New York. I studied with Stuart Davis, who is a very well known painter and the world’s worst teacher, a terrible teacher. We met once a week, in the evening, and once at the end of the class he said, “All right children, let’s close the magic portals. We’ve conjured up enough art atmosphere for one evening.” You know, for an idealistic kid – by that time I think I was about eighteen or nineteen — that’s not what you want to hear. So, I heard from my brother Peter about The Hofmann School. That’s where everybody went in those days, anybody who was anybody. He was known to give you a foothold in modern art, and a valid one. My brother was there already, and I joined him in The Hofmann School. Since I spoke German, and Hofmann hardly spoke English – he’d say things like, “This picture is too bunt.” People would look at him and they’d look at me, and they’d say, “What does he mean?” I would say that “bunt” is a word that doesn’t exist in American, because it just means disorganized color, like circus colors, or something like that. If he says your picture is too “bunt,” it means that it’s disorganized chromatically.

Through that, people started to understand what he meant, and I became his assistant in the school, and then I became the monitor. When the GI Bill almost ran out and I could see that I’d better hold on to what I had left of it – I think eight months I still had going – I quit the school and I became Hofmann’s studio assistant. While working for Hans Hofmann, I got to known him much better and having more and more respect. It was exaggerated respect of him, because he was a very, very fascinating personality. He was born knowing more about life than most people learned their whole lifetime long. Exaggeration, but nevertheless, I had really an extraordinary respect for the man. Then I started going out into nature and making drawings, because I was trying – I was influenced at that time by Rembrandt drawings that he made in Holland from nature. I showed these to Hofmann, and he said, “Maybe you’d better stop doing art for a while, because you’re suffering from mental indigestion.”

In fact, I was quite unhappy in those days, because I could see I wasn’t getting anywhere. So, I applied to the University of Chicago, and I got accepted, which in those days was much easier, especially for GIs, than it would be now. I went to Chicago and attended for one academic year and graduated after eight months. So, right at the end of my GI Bill, I also got a degree. The funny thing is just recently I got a letter from Chicago saying that I was going elected as the outstanding graduate for my year, at the next commencement in Chicago, and they invited me to come out there. Of course, I felt this was quite something, so I may go to Chicago next May. But, after eight months, what do they know? Then I got this scholarship to go to School of Humanities, because this art history professor got an interest in me. In addition to a scholarship, I even got a stipend, $2,000 a year, which in those days you could live on. Also, I researched where you could make the most money as an unskilled worker. I found out, if you went to Alaska to do road work, or if you went in the woods in the Northwest – so I heard that the mosquitoes in Alaska were dive-bombing people, and it was uncomfortable, so I decided to go to work in the woods, which I did. While there, I regained all my confidence, and I decided I’m not going to go to any school, I’m going to go back to being an artist. I was making drawings in the woods and so on. Then I came back to New York and, at that point, the Hofmann people found a space to rent to start a cooperative gallery, of which I was one of the founders – the Hansa Gallery. That’s how I had my first show. I guess my first show elicited some attention from critics, including Fairfield Porter, who was at that point already quite a well known painter, and Bill de Kooning. He was a friend of mine in those days too, when I first got started back in the art game.

Then I became part of the scene, the second generation New York School. After that, nothing more very exciting happened, except I got married and I went Italy. Everything sort of happened naturally. I never believed in trying to forge a style or anything like that. In fact, my early paintings and drawings were very influenced by Van Gogh and by Bernard. I never cared about that, because I figured if I have any kind of thing to say or a personality of my own, it would come out anyway, whether I tried for it or not.

TRACK 03 – ART / COLOR / PROCESS

In my own work, I was still holding onto sort of Van Gogh-y kind of involvements. But then, living in Venice and looking out at the Maritima, the big body of water with the tour boats coming up, I just – it affected me and changed my whole style, my whole way of getting involved in art. And I ended up painting mostly all white paintings because I thought the light of Venice was sort of milky. I mean, it ended up being milky and white for me. The way I was painting then, which was all in grays and whites, was so difficult that it took some of the joy out of doing it. Then one summer we went to Maine, and we lived on the southwest harbor of Deer Isle, Maine. In the evening I looked right into the sunset, down this cove into a sunset. And the idea of painting that in all gray would have been unnatural, so I started becoming involved in color again.

What I really believe in is the eye. I think you’ve got to get the mind sort of out of the way and trust that the eye will do things far more comprehensively and more interestingly, certainly, than what you can think about. So I always try to get my painting to the point where the painting speaks to me, rather than me speaking to the painting. I have a feeling at that point, you get in touch with things that are truly interesting and truly mean something, because you’re beyond convention, what have you, you know, and normalcy. I’m against normalcy. I try to get beyond intention. There, of course, the person who most influences me in that search would be Pollock, because he really wanted to get beyond intention, as soon as he started, practically. That’s really his revolutionary influence. The thing is that people don’t realize how important that was, but that connected him and me, and whole lot of other people, including the abstract expressionists. He connected them with surrealism and automatism, and all these tendencies, which I think most people don’t even understand, but which guide me in my work all the time; because I want to be able to see what the picture needs, rather than to start thinking about it. I think it’s pretty close to what happens, that you try and get beyond where you’ve been, because to do over again what you’ve done before – I mean, if you’re a scientist that would be a sin. You don’t do experiments over again that other people have already done. As a painter, I think you shouldn’t expose the public to things they already know, almost as an obligation. You have to take them beyond where things are easily explained.

Of course, being as I am, I think of myself as a very conventional person, very ordinary person, but I do believe that one of the obligations of an artist is to go toward transcendence, and not necessarily to have that as an obligation that weighs upon you, but to have a prospect in your work, or a natural development in your work, that leads you there. In that sense, I’m quite different from most of the landscape painters I know. I think I’m quite different, certainly, from the conceptual artists and people like that. So, even though painting appears not to have reached some kind of a high point right now, still I have a feeling it’s worth doing, because you’re in touch with some kind of natural process. And that seems valuable to me, you know. That’s good enough for me to keep going.

Copyright Story Preservation Initiative. All rights reserved.

One Response to “A Conversation with Artist Wolf Kahn”

[…] “The artist has but one idea,” noted Henri Matisse. “He is born with it and spends a lifetime developing it and making it breathe.” Wolf Kahn, 86, one of the most important colorists working in the U.S. today, has spent six decades making his work breathe. His latest exhibition, Wolf Kahn: Six Decades, continues at Ameringer McEnery Yohe (525 W 22nd Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) through May 31. Read a current interview at Hyperallergic. Learn more about Wolf Kahn and hear interviews at the Story Preservation Initiative. […]